Chocolate Prices Have Spiked. Why Are Cocoa Farmers Still So Poor?

Emmanuel Frimpong, 32, is a cocoa farmer in Ghana, mostly by default. He has a university education but couldn’t find another job so he works on the family farm. “Why not?” he told me. “I’m willing to do the job.” His literacy and English skills help him serve as a liaison between his fellow farmers and the government, which is the primary price-setter for cocoa beans in Ghana.

The exorbitant prices paid for cocoa beans and chocolate products in the United States and other nations barely touch the lives of Frimpong and those around him. “The living conditions are very poor,” he told me. “The water system is very poor.” The government’s payments for cocoa beans are “a little bit low” and its support for the farmers — for example, a pesticide sprayer that must be shared by more than 100 families — is “woefully inadequate,” he said.

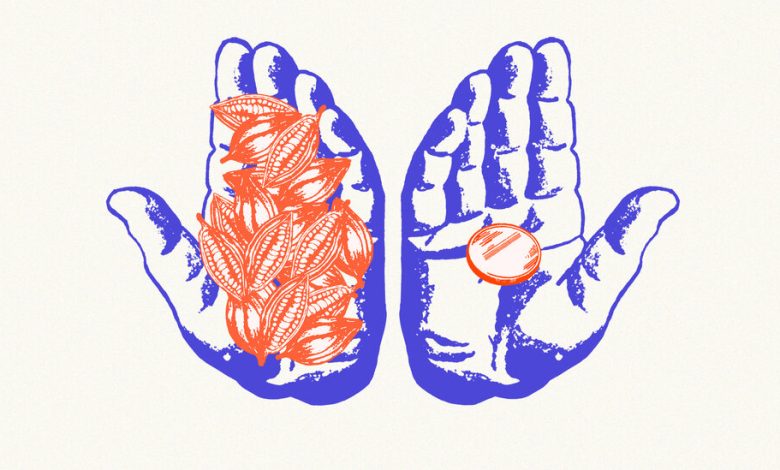

The poverty of cocoa farmers is sometimes seen as a moral failing of chocolate buyers or sellers, but above all it’s a market failure. In a healthy market, price spikes are self-correcting: When the price rises, production increases to take advantage of the extra profit opportunity. But farmers in Ghana and neighboring Ivory Coast, the world’s No. 2 and No. 1 cocoa-producing nations, aren’t feeling the love. Most live in poverty. They don’t have the funds for long-term investment in new cacao trees, which are the source of cocoa beans, or for adequate fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation and labor-intensive pruning.

Some farmers put more land under cultivation to compensate for falling yields, which involves cutting down primary forests. Many put children to work. Some are giving up on cocoa and turning to growing maize or rubber or selling their land for illegal, environmentally destructive open-pit gold mining.

The poorer the cocoa farmers get, the higher the prices of cocoa and chocolate rise on the world market, because the under-capitalized farmers produce fewer beans or give up entirely. It’s a destructive dynamic, or a “low-income trap” in the phrasing of the International Food Policy Research Institute.

Farmers in Ivory Coast and Ghana aren’t getting the full benefit of the run-up in world prices because of a 2018 agreement called the Côte d’Ivoire-Ghana Cocoa Initiative. Intended to protect farmers from price volatility, it enables governments to establish price floors by auctioning off purchase rights to the major international buyers, which have the option to pay premiums to individual farmers for reliability and environmental sustainability.