I woke up to yelling in the hallway.

A few seconds later, there was a bang on the door.

It was just after 2 a.m., and a state trooper in the hallway of our private living quarters at the governor’s residence said there was a fire in the building. We needed to evacuate immediately.

My wife, Lori, and I ran to the bedrooms where our kids and two dogs were sleeping. We got them up quickly and followed the trooper down a back stairwell to the driveway.

At that point, standing in the cold, damp air, knowing that all the kids were accounted for, we began to wonder what had happened.

We thought it must be some kind of accident — perhaps a candle had been left burning and tipped over, something had short-circuited or there had been a malfunction in the kitchen.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

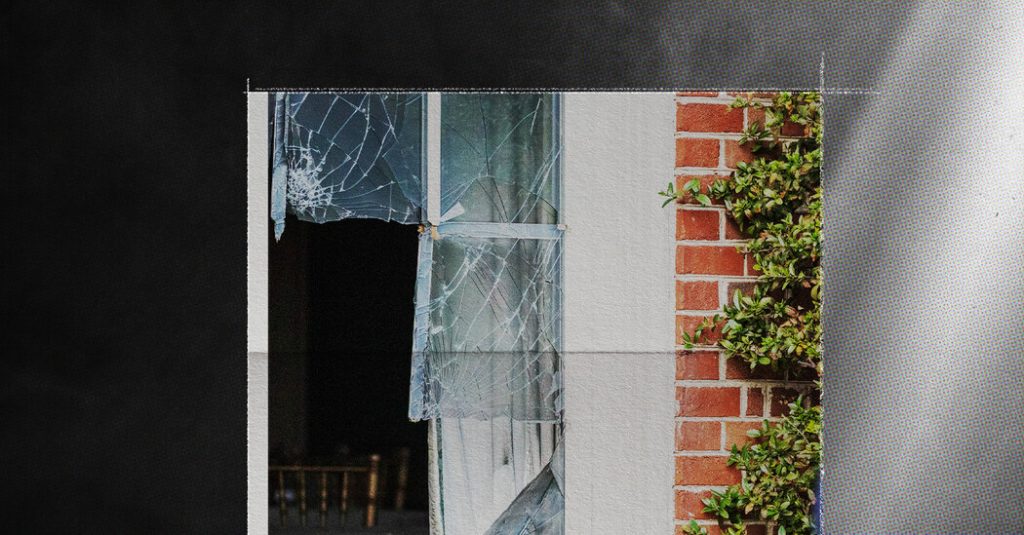

But once the fire was extinguished — and firefighters were tackling the last few hot spots — the chief of the Harrisburg Bureau of Fire took me back inside to see the damage.

As I walked through the doorway, my nose burned from the smell of smoke. It was eerily quiet, but I could hear water dripping from the ceiling. My feet sloshed on the soaked floor.

Subscribe to The Times to read as many articles as you like.